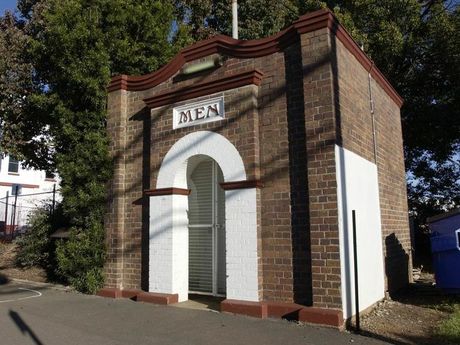

- Do you know Toowoomba has a heritage toilet?! The urinal was built in 1919 and is situated in Russell Street opposite the railway yard. The immediate social context for the urinal is to be found in the relevant history of Toowoomba. By the late nineteenth century, the lack of sanitation in Toowoomba became a pressing local issue. Earth closets were in a disgraceful condition and typhoid fever was prevalent. It was in these circumstances that Toowoomba’s health program, and that of Queensland generally, began to take shape. Boards of Health were established but no real success was achieved until the first years of the twentieth century. Despite improved sanitary services, Toowoomba had 98 cases of enteric fever (typhoid) in 1916 although by 1918 this had dropped to 17. The foremost mover in these plans was Dr T A Price, public health advocate and mayor of Toowoomba in 1919.

The lack of a sewerage system had a major effect upon the provision and type of sanitation, especially for public toilets. Until a sewerage system was installed, all public toilets either had to be in a location where they could be cleaned by a pan service or else operated purely as urinals where the urine could be flushed away to a drain as normal dirty water. A pan service could scarcely be provided in the middle of busy city streets. It is for this reason that women’s toilets were located in buildings or some discreet spot, while men could enjoy the use of dedicated urinals in the streets. This was the situation in Toowoomba until 1919. Public toilets with closets were available at the Railway Station for both men and women and there were a number of iron urinals for men in the streets of the city. These iron urinals were equipped with a water tank for the purposes of cleansing. They operated successfully, but in 1918, the Council recommended their removal and planned better facilities. This is when the new toilet in Russell Street was planned and built.

The original plans are unsigned but were probably drawn by the Toowoomba City Engineer, Mr Creagh. The urinal stalls were originally connected to the nearby drain; the closet was cleaned by a pan changing service. The whole ensemble was only connected to the sewerage system in 1926. The manhole covers at the rear of the toilet may date from the time of the sewerage connection. In 1933 plans were made to alter the building but these were not carried out. The building was originally set in a ‘rockery and garden’ which may have been destroyed after the Second World War. Certainly nothing now remains of the original rockery except perhaps the palm trees at the rear of the toilet.

Several factors were involved in the choice of the site. The building was an independent and free-standing toilet which needed both a urine draining system and a pan cleansing service. It therefore had to be near a drain and there had to be space and cover for the pan-changing operation. This may account partly for the location and the associated garden. Not only was the toilet built practically on top of a main drain, it was an easily accessible location, both for users and for the sanitary service men, and with sufficient room for a little garden of modesty and salubrity. A second factor concerns urban design. Dr Price wanted ‘… a healthy city, a convenient city – good roads, good footpaths, and an easy way of getting about, a beautiful city with trees and parks and gardens.’ This linking of urban health to urban beauty fits the urinal neatly into a scheme for making the area around the railway station more attractive. There were plans to improve the railway precinct and these may have influenced the decision to site the little building with its garden at the city end of the railway station. The street facade of the urinal is certainly handsome enough to suit an urban beauty program. Indeed, this secondary role of urban design may explain why the toilet has quite such a delightful facade. In this sense, urban beauty became a sign of urban health.

Being between the railway station and the main part of the city, the toilet was very handy for as many people as possible provided, of course, they were men. There were women’s toilets in the city, but generally more public toilets were provided for men than for women. The Russell Street urinal, taken in this context, is a visible example of the difficulties women had in managing a public life. But the urinal also demonstrates something of the lack of impact of technology upon women’s public lives. The Russell Street urinal served as a model of how a full sanitary service could be provided in an open public place; and when it was seen to be successful, calls were made to extend the service to women. But the calls were not heeded, and even when a sewerage service was fully operational in the second half of the 1920s, the Council provided no toilets for women. Women had to take the issue up themselves. In 1931 the Country Women’s Association lobbied the Toowoomba City Council for provision of lavatory accommodation for women and children. The Council did nothing and the women had to provide for themselves by opening the CWA Rest Rooms in Margaret Street in 1931.

Up until the early part of the twentieth century, the design of dedicated urinals was commonly of the iron pissoir variety (properly called a urinoir) which comprised a decorated iron screen formed into an appropriate spiral shape for both convenience and modesty. They came in single or double versions. There were a number in Brisbane, one originally in Merthyr Road now relocated in Newstead Park. They were made in Brisbane by Evans, Anderson & Phelan. The Russell Street urinal represents a kind of transitional design between the iron pissoir and the fully fledged toilet building. Like the pissoirs, the Russell Street structure has no roof and is designed with a screen instead of doors for maximum convenience. (Only the internal closet has a door.) Public toilets erected immediately after the Russell Street urinal are complete roofed buildings as, for example, the splendid set of lavatories in Toowong Cemetery of 1924. Part of the impulse behind this transition from modesty screens to complete buildings may have been the desire to make the actual style and design of the toilets indicate something about health. The Russell Street urinal is the only known ‘transitional’ toilet design in Queensland.

The history of drainage, sanitary services, sewerage systems and public toilets takes its place within the general history of public health in Queensland. Improvements in drainage and sanitary services have done at least as much to procure good health and save lives as any other branch of medicine. This general trend can be traced in Toowoomba very clearly; and the little urinal in Russell Street, in the context of its site, provides much evidence of this achievement.

Recent Comments